Sources - The 1832 Pensioners

The information used to build the dataset behind the Jersey militia veteran migration maps comes from the Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application Files, NARA Record Group 15, Microfilm Publication 804, held by the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. After transcribing 3,164 pension declarations filed by New Jersey veterans and widows on Fold3.com, I separated out the cohort of veterans who applied to receive benefits under the Act of 1832, which, as of June 2025, numbered 2,005 declarations.

The Act of June 7, 1832 finally achieved what William Henry Harrison, then a Representative from Ohio, had hoped back in 1817, while debating the merits of the first Revolutionary pension act. While he objected to allowing anyone who served from being granted a pension as it would “embrace everyone who had shouldered a musket, even for an hour… Persons, however, covered with scars and borne down by the length of service in those days ought not to be confounded with those who had been called out for an hour or a day.” Yet, he conceded that “[s]ome of the militia, he thought, were as well entitled to this pension as any regulars, of whom the Jersey militia might be particularly mentioned.” Once passed, so many New Jersey militiamen applied under this new Act, that John Blowers (S.2381) and Daniel Skellinger (S.4844) would refer to it as “the militia pension law.”

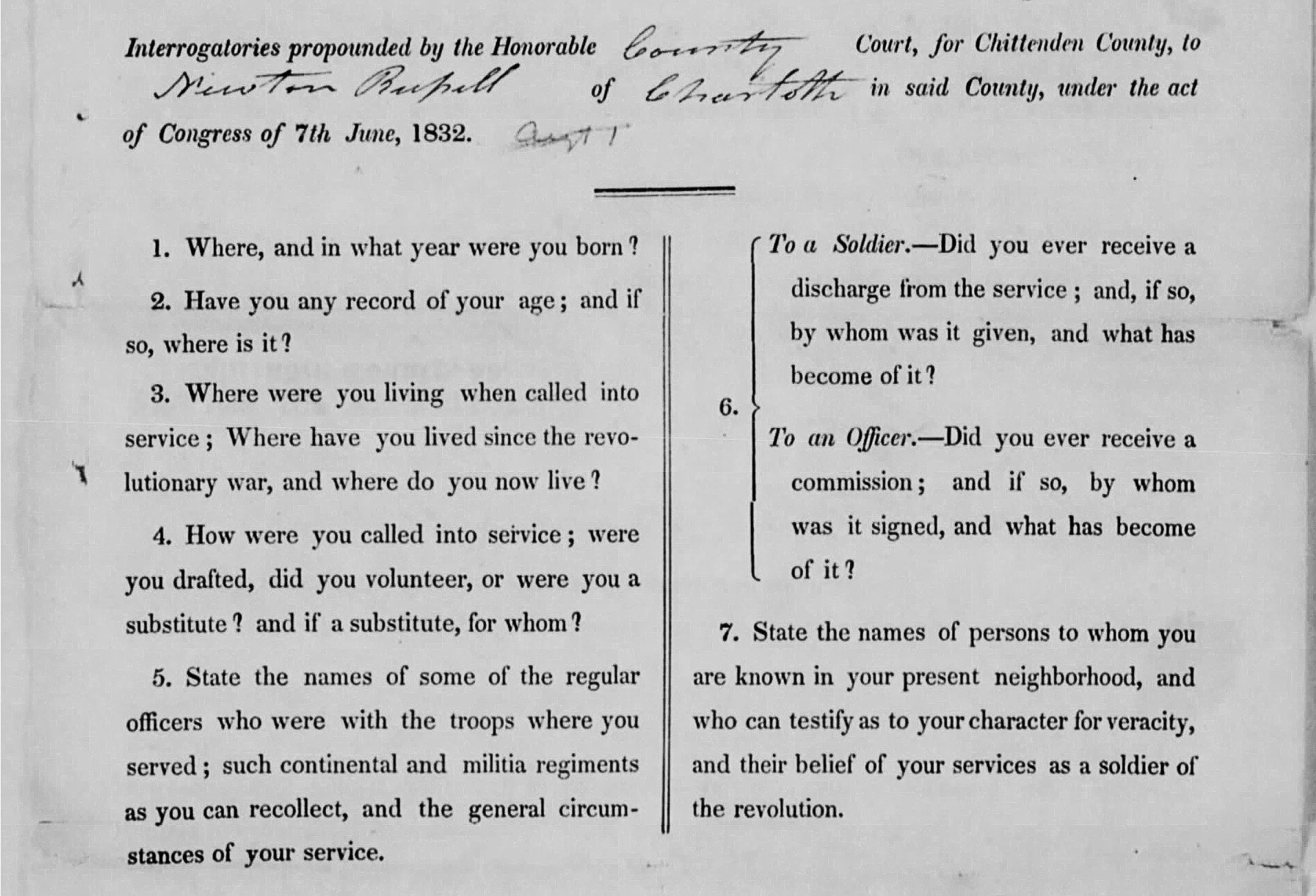

Because the War Department now had nearly 15 years of experience accepting declarations filed under the Acts of 1818 and 1820, firm regulations for all future applications under the Act of June 7, 1832 were established, and a two-page printed copy was sent to courts and pension agents across the country.

Copies of the complete “Regulations Under the Act of June 7, 1832” are often found within a veteran’s pension file. This copy was included in the file of Private Thomas Scroggy (W.988), who made his declaration on applied on November 26, 1832 and was approved for a yearly sum of $41.66.

The Interrogatories

The greatest obstacle faced by veterans applying under the Act of 1832 was in documenting their services. The vast majority of these men served in the militia, which left a very sparse paper trail compared to the regular Continental army. Few pay and muster rolls survived, and those that did formed a very incomplete picture of a soldier’s service. Most militiamen served tours lasting about a month, turning out on active duty for 30 days, then returning home for 30 days, alternating duty to other militia companies or classes of companies every other month. Discharges for this type of short-term service were verbal. Written discharges were reserved for longer terms of service, such as for Robert Gould’s one year under John Outwater in the New Jersey State Regiment in 1781, or John Campfield’s term as a nine month levy in the 1st New Jersey Regiment in 1778.

Since there was little documentary evidence, the War Department had to rely on traditional evidence from applicants under the Act of 1832. Veterans gave oral testimony, supported by at two “credible witnesses.” The interrogatories guided the court in collecting the right information to accurately determine whether a veteran did indeed serve during the Revolutionary War.

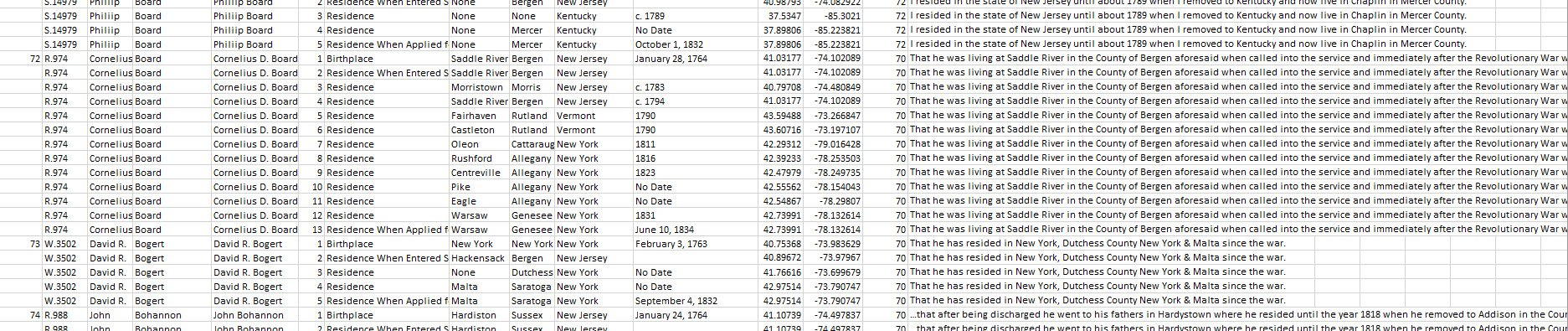

The responses to question number three formed the dataset behind the maps showing the migration and location of the 1832 cohort of veterans. It revealed that New Jersey’s Revolutionary veterans were a highly mobile people, many of whom moved multiple times across large distances over the course of their lives. While some veterans remained close to home, some, such as Cornelius D. Board (R.974), who moved a total of 13 times by the time he was 70, and finally settled in Warsaw, Genesee County, New York in 1831, where he applied for his pension on June 10, 1834.